Introduction – What digital marketing channels provide the best ROI?

Maximise Your PPC Campaigns: How to Calculate ROAS and CPL

We currently run and have run several different company-owned websites, including comparison websites and lead-gen websites.

We focus on providing three services to generate website traffic for our clients and our websites. We initially started with SEO, then we added PPC, and in recent years we have also begun to provide paid social. Some of our websites operate on an affiliate model, and we strongly encourage our clients to adopt this.

We chose to provide these services because of the high intent of the traffic from these sources. When people search for something, they are already in the market for taking action in some capacity. Paid Social is less so, but the granularity of the audience targeting mitigates this, so whilst they aren’t necessarily searching, they do have an active interest, and they can be in the right location and be of the appropriate demographic. Affiliate Marketing is the least targeted, but as you only pay on a lead or sale, this is effective, as it puts the onus on the websites that show the affiliate ads to generate high-quality traffic.

Many people can make a good website, but how do you get it known by people? Then beyond that, how do you get people to transact from it? Further to this, how do you scale? These are all essential parts of the process, but with this article, I will focus on creating a PPC campaign that produces an ROI.

Let’s start with the basics.

Keyword Intent – How to categorise keyword research?

Several years ago, we devised our categorization methodology for segmenting keywords into groupings based on the “phase of intent”. Our model looks at segmenting keywords into four phases of the customer journey, starting with “idea” and moving to “browsing”, then to “comparing”, and then to “purchase”.

SEMrush, among others, uses a slightly different methodology, breaking keywords down into commercial, informational, navigational, and transactional. The language here could be more fitting because, in terms of terminology, this doesn’t follow a journey.

Everything starts with an idea, and this is when you go to Google (or another search engine) with no real intent to purchase but may wish to find something out; for example, researching a topic. As you refine your keyword search, you become more qualified in what you are looking for until you eventually reach a point where you wish to purchase.

Methodologies – Why do old marketing methodologies no longer apply to digital marketing?

Some people will try to apply older methodologies, such as the Marketing Rule of 7; unfortunately, these work differently from conventional ones. The ineffectiveness of this methodology becoming outdated is potential because people will become aware of different products and services at other times in their lives and throughout different experiences; it is different in 2023 from how it was in 1930. I state this because the number of times a service or product must be seen in the digital world will vary. Information can now be delivered concisely or in-depth via video, interactivity, emails, articles, or other means. In addition, there are ways to lower the barrier to entry by providing insights, samples, or outcomes that were not available when the noted methodologies were coined.

What we are considering at this stage is that people go to Google (or another search engine) to buy a product or service without necessarily knowing which company will provide the product or service. There are indeed many different keywords at many different phases of the journey, including those that are aware of the available providers or have a specific provider in mind; however, with this example, we are most interested in those that are very much aware of the market, the type of product or service that they are looking for, but not the specific provider.

What assumptions are made in this article?

In this article, we assume that you know metrics such as cost-per-lead (CPL), return on ad spend (RoAS), and all the available metrics shown within the Google Ads platform on both measurements. If you still need to, please read this article.

Instead of delving into these aspects, in this article, we will focus on the maths behind making a campaign profitable and the restrictions preventing a PPC campaign from succeeding.

What is Attribution?

This guide also assumes a basic understanding of attribution. Attribution is at what point(s) in the journey the conversion is apportioned. There are multiple attribution models, with ‘Last Click’ being the most common historically, where all conversions are 100% attributed to the last interaction. So, no matter how many parts of the journey there were previously, the last click is given the entire conversion attribution weighting. There’s linear, which apportions each interaction equally; for example, if a visitor searches on Google, clicks on the ad, then sees a remarketing ad on Facebook, then decides to Google search and then finally visits the website directly, each one of the four stages would be given 25% of the conversion attribution.

Attribution is much more complicated than this, as an interaction occurring at a specific part of the process could influence the conversion journey without it being obvious. Accurate attribution could only be possible by looking at all trips to see where the interaction was placed in the customer journey and then correlating this to the conversion rate. Checking the conversion rate correlation at any point in the customer journey versus the correlation at a specific part of the journey would help establish the weighting.

Google’s data-driven modeling will likely look at this, but we will only look at this in further detail at this stage.

CPC Bids – What is Cost-per-click?

Let’s start with the fundamentals, CPC (cost-per-click) bid prices. A CPC is how much you pay per click, and CPC bids are an auction, resulting in whoever pays more showing higher.

More recently, Google has moved to include TCPA (target cost per acquisition) and target ROAS (return on ad spend). This is great (in a way, as it makes it easier), but it gives responsibility to Google, along with obfuscating the data so that you can’t see what is going on. If you use this strategy, you must investigate and optimise the lead value. At the same time, ROAS shows you the value (but may not show you the actual lifetime value).

CPC can be impacted by keyword quality score, and your Ad CTR could be impacted by ad strength – an excellent ad strength and a 10 out of 10 for keyword quality score is what you aim for. Ad strength does not impact CPC or quality score.

Below is an infographic showing how quality scores can impact CPC:

As shown above, you will pay more for the click if you have a lower quality score. This is particularly important if you have a fixed budget, as you want to get as many clicks as possible. I say this with the significant caveat that you do not want to sacrifice the quality of clicks in favour of getting more clicks; you want to get more high-quality clicks for less cost, and I shall explain why in the article below.

This visual representation below shows how inefficient spending can be improved by improving quality scores.

How do CPC prices vary?

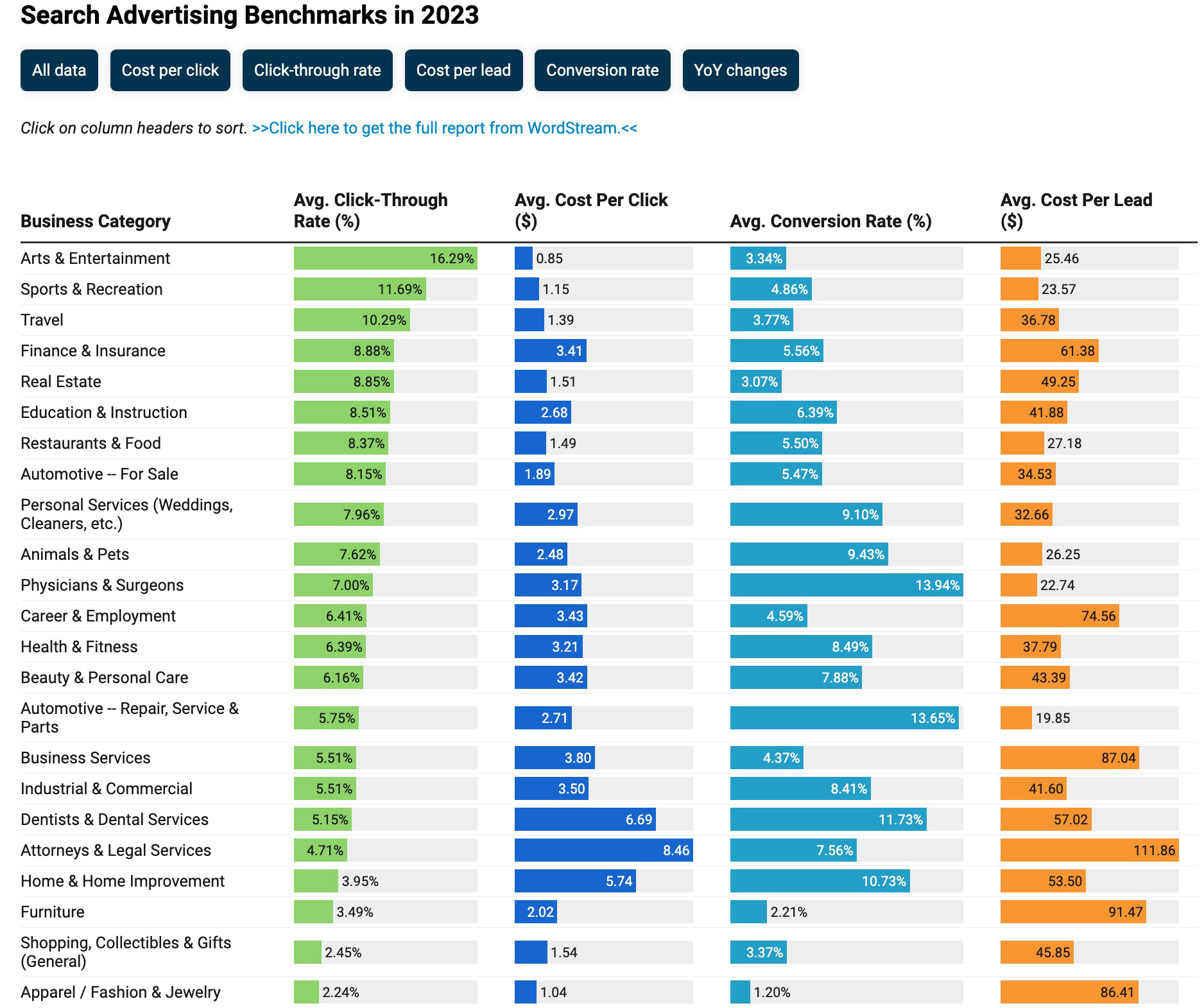

The infographic below shows that CPC prices can vary based on your industry. This happens for several reasons, and one such reason is that companies are willing to pay more per click because the leads or sales are more valuable to them. This may occur due to them having higher margins or a high conversion rate from click to lead or click to sale.

How to calculate the cost of sales?

As I have outlined previously in videos and articles, you need to consider the conversion rate of clicks to leads/sales.

The data below shows the cost per lead, but it needs to show what the lead is worth.

By using ‘physicians and surgeons’ as an example from the table below, we can see that the CPC price is $3.17, the conversion rate is 13.94%, and the average cost per lead is $22.74.

The budget was $50 per day, and the number of days in the month was 30; therefore, we would have a $1,500 budget. A minuscule budget, but in this example, this is highly relevant.

We can estimate the total number of leads by dividing the entire budget by the number of leads. Rounding down, this would be 26 leads per month.

Let’s say the end customer is worth $1,000. Let’s also say that the average lead converts into a customer one out of every five times (so 20%). This means you spend five times $22.74, therefore $113.70 per customer.

Based on this calculation, the acquisition of customers sits at 11.37% (the cost of sale figure) – a decent CoS. This is particularly good if the client’s profit margin is healthy. Understanding the client’s margin would be best, so it’s 30% after all costs.

This is where agency fees become a problem. Suppose our agency fees are $1,000 per month. In that case, the total monthly budget is $1,600 per month divided by the number of leads generated; therefore, $1,600 / 26 gives a cost per lead of $61.54, and multiplying $61.54 by five increases the cost per customer to $307.70; consequently, a 30.77% cost of sale. At this point, we’ve nearly tripled the cost of sales, thus rendering the campaigns ineffective. Most importantly, as mentioned above, the client margin is 30%, so we are now running at a loss.

The solution:

1. They manage the campaign themselves, as they aren’t going to stay as a client very long. Cancel the client before they cancel you – they will, and all parties should end the relationship if they can’t afford to go big on spending.

2. We increase the budget. Increasing the budget by double, triple, or even quadruple isn’t going to cut it.

Not only will increasing the budget increase the number of leads, but it will also diminish the proportion of marketing spend resulting from our fees.

Let’s rerun this scenario based on the exact fees and a ten-times bigger budget.

The budget is now $6,000 per month. This means they are generating 260 leads per month and, therefore, 52 new customers per month based on the same conversion rates from lead to sale. We are ignoring that further refinements from the campaign could result in better quality inquiries, better quality customers with higher average transaction values, and an increased conversion rate from the lead to sale based on improvements and optimisations in the campaign.

These numbers mean the total marketing would be $7,000 per month. $7,000 / 260 is $26.92 per lead, and $7,000 / 52 is $134.62, including fees at the cost of sale of 13.46%.

The idea would be to continue refining the performance to align with the CoS performance, excluding that of the agency fee, thus rendering the agency fee an improvement in ROI and, therefore, speculation to accumulate.

What is the impact of discounting on profit margins?

Fundamentally, discounting impacts your profit, and you need to increase sales substantially to make the same revenue when applying discounts.

This article explains more: https://www.profitwell.com/recur/all/how-do-discounts-impact-growth.

How does discounting improve performance?

Discounting can decrease profit due to lower margins; however, when combined with bulk orders, related products, multi-buy products, or increased service levels, this can improve the revenue generated.

Because the conversion rates increase and the transaction value increases while keeping the CoS or CPL the same or similar to previously, this results in an improved ROI.

How does discounting relate to increased cost per lead or CPA?

Increasing CPL or CPA has an impact because it’s effectively equivalent to discounting. Increased CPL mirrors discounting because you are diminishing the margin, so you need to generate proportionately more conversions to seek the same returns. With a limited budget, you cannot spend sufficiently to cause increased conversions. The fewer clicks, the longer it takes to generate sufficient clicks to achieve the conversion rate. You might obtain a conversion within a few clicks or even on the first click, but this would be anomalous and eventually average out.

The table above reflects CPA relative to COS, whereas the graph below shows profit relative to CPC. The only way that this can produce success with either example is if sales grow exponentially.

How to calculate ROAS?

Here are three example scenarios:

Scenario A:

The product is £120. The product’s margin is 50%, which is £60. They want to spend half of the margin (25% of the total), thus £30, on acquiring the sale.

From a spend of £300 per day, they generate ten sales at the cost of £30 per sale.

The conversion rate from click to sale is 10%, and each click costs £3 per click.

The campaign runs for 20 days and gets 200 clicks from a spend of £6,000.

Outcome.

They generate £1,200 per day, so £24,000 over the 20 days.

Scenario B:

The product is £120. The product’s margin is 50%, which is £60. They want to spend half of the margin (25% of the total), thus £30, on acquiring the sale (all the same as above).

From a spend of £300 per day, they generate ten sales at the cost of £30 per sale (also the same as above).

The client wants to increase sales, so the agency increases the bids by 20% to £480.

Outcome:

The increase in CPC to £4 increases the CPA to £40, and the budgets remain the same at £300 per day; therefore, they can only generate 75 clicks per day and thus 1,500 clicks per month. The outcome results in 150 sales and revenue of £18,000.

The revenue is £18,000, so £6,000 (20%) less than Scenario A, and the cost of sale is 33.3% rather than 25%.

In this scenario, the conversion rates and the average transaction value would improve for a better return.

Scenario C:

The product is £100. The product’s margin is 50%, which is £50. The client wants to spend half of the margin (25% of the total), thus £25, on acquiring the sale.

The conversion rate from click to sale is 10%, and each click is £4 per click.

This time they are willing to increase the budget by double, increasing spending to £600 per day.

Outcome

The result is 15 conversions, a revenue of £1,800 per day, thus £36,000. The spend is £12,000, so a 33% cost-of-sale; however, the revenue has increased proportionately.

Profit Breakdown:

Scenario A: (£24,000 * 50% –

Scenario B: (£18,000 * 50% –

Scenario C: (£36,000 * 50% –

At face value, scenario C looks excellent, with the increased revenue, but there’s nothing more gained in profit. The profit is still £6,000 with more products to ship, store, pick, and pack, so the end gain will ultimately be even less than Scenario A.

The profit would have to be much higher for Scenario C to work. In addition to more sales, there should be improvements to conversion rates and average transaction value, or the cost of production or purchase and profit margin should be improved by the product supplier.

Let’s bring this back to profit vs. CPC.

To help visualise this, I have included a graph below showing how profit will diminish after a certain point.

How Economies of Scale apply to digital marketing.

Using economies of scale (as mentioned above regarding cost of production) can be an effective way to grow a business; however, economies of scale sometimes work differently regarding PPC. Economies of scale work by reducing the cost of production in line with an increase in sales; therefore, the percentage of that cost of production diminishes. The above example regarding agency fees versus spend is precisely that.

How focusing on high-quality leads can reduce performance…

My final point in this article is that concentrating purely on high-quality leads can reduce performance.

Every keyword has a conversion rate, and every landing page has a conversion rate, which can vary wildly.

However, for this example, we need to set a conversion rate as the average total across all landing pages and keywords for the ease of understanding.

1. In this example, the client has a budget per day of £100. Clicks cost £20 per click on average, for five clicks per day.

2. With a conversion rate of 1%, that’s 20 days and £2,000 before they get a conversion.

Achieving this result is fine if the margin is there, but the client wants to see more leads and sales, as they are measured on this, so receiving a lead every 20 days does not cut it (as this is a meagre 18.25 leads per year)

The client needs to get one lead per day for the same budget. They state this because they have fixed overheads and must generate sufficient revenue to maintain them. This outcome is understood to be the case because 1 in 5 leads converts to a customer, and each customer is worth £10,000. Based on the 18.25 leads per year, this would be 3.65 sales.

How many clicks do we need, and how much do we need to reduce the CPC?

Let’s take the budget and work from there; at £100 per day, we know that they have a conversion rate of 1%, so we need 100 clicks and, therefore, a £1 CPC to do so.

The issue here is that reducing CPC will likely diminish impression share, and it’s not a linear correlation, but we would see a substantial reduction. It may work, but there’s a risk that doing so rarely shows the ads, which renders the campaign ineffective, as shown in the screenshot from PPC Hero:

Solution:

At this point, we end up focusing on high-quality leads.

Let’s assume that from the data (not shown), we can see that Pareto’s principle applies and that 20% of all keywords generate 80% of sales. This 20% of keywords perform a higher lead-to-sale ratio of 1 in 2, and 80% of leads convert to a sale in 1 in 10. For ease of understanding, let’s also assume that there’s an equal apportionment of clicks across all keywords (highly unlikely, but it’s easier to understand with this being the case).

The Top 20% of keywords generate a TPCL at £100, as do the bottom 80%—assuming this makes the equation easier also. These leads convert at 1 in 2. The Top 20% generate a sale for £200.

The bottom 80% of keywords generate a sale at £1,000; these leads convert at 1 in 10.

Let’s remove the bottom 80%, focusing purely on the top 20% due to the limited budget. We understand we can go up to £500 per lead because they want to spend £1,000 on every £10,000 customer (a 10% CoS and a 5% CPL excluding agency fees, ignoring agency fees for now).

Increasing this by £500 per lead pushes us to £5 per click, and budgets remain the same (at £100 per day), so we only get 20 clicks daily. As a result, we then see that we get a lead every five days and a sale every ten days. This results in 3 sales per month at £30,000 from a £3,000 spend. In our eyes, this is successful, but the client wants leads at a rate of 1 per day. This works if they are willing to evaluate sales revenue over the year, but if they measure lead volumes, this also doesn’t work.

Improved solution:

We need to maintain a balance of high-quality leads with volume.

In this instance, we reduce the CPA of the bottom 80% of lead quality keywords to 20% of CPC and the CPA of the Top 20% of keywords and keep the Top 20% of keywords at the correct and optimal CPA. This means we support the volume of leads balanced with the quality.

Final comments

If the client has a fixed budget, you are limited to working within this until you prove ROI and they increase the ad budget for the next financial year. In the interim, here’s a final suggestion to help improve performance:

If your budgets are being reached each day, establish how much impression share you are losing.

Notch the CPA down (or the ROAS up) by the proportionate amount.

If you find that this reduces your impression share too much and you aren’t spending anywhere near the budget, then notch the CPA back up, but not quite to the original level.

Continue to calibrate the CPA (or ROAS) until you accurately reach the budget without underspending or overspending.

Footnote:

I’ve used CPA and CPL interchangeably here. CPA is the cost per acquisition, and CPL is the cost per lead.

TLDR:

ROAS (Return on Advertising Spend) is a metric that measures the revenue generated by advertising campaigns in relation to the cost of the advertising spend.

The cost of sale (CoS) is a metric that measures the cost of acquiring a sale and is calculated by dividing the total advertising spend by the number of sales generated.

To improve ROAS, focus on high-quality leads and adjust bids to maximize ROI.

To calculate ROAS, divide the revenue generated by the advertising spend.

Optimize campaigns for high-converting keywords and landing pages to reduce the cost of sale and adjust bids to maximize ROI.

Use economies of scale to reduce the cost of production in line with an increase in sales.

Concentrating purely on high-quality leads can reduce performance; maintain a balance of high-quality leads and volume.

If budgets are being reached daily, establish how much impression share is lost and adjust the CPA (or ROAS) until the budget is accurately reached without underspending or overspending.

Monitor performance regularly, refine and optimize campaigns as necessary, and adjust budgets and bids to maximize ROI.

Sources:

PPC Hero: https://www.ppchero.

ProfitWell: https://www.profitwell.com/

Google Ads Help: https://support.google.com/google-ads/

Wordstream: https://www.wordstream.com/

Search Engine Journal: https://www.searchenginejournal.com/

Neil Patel: https://neilpatel.

Hubspot: https://www.hubspot.com/

Tips:

Conduct keyword research to identify high-converting keywords and optimize landing pages for those keywords.

Use negative keywords to filter out irrelevant traffic and improve targeting.

Create compelling ad copy that is relevant to the keywords and landing pages.

Set realistic goals and track performance regularly to identify areas for improvement.

Continuously test and optimize campaigns to improve performance.

Consider using automation tools to save time and improve efficiency.

What’s next?

To utilise this guide to its full potential, first, you must understand your client by asking the following questions:

What is your profit margin?

What is your average transaction value?

What are the barriers to buying your product or service?

What are your USPs?

Who are your primary, secondary, and tertiary competitors?

Fundamentally, without understanding the client’s financials in detail, it is very difficult to build and optimise one or more campaigns that produce a ROI.